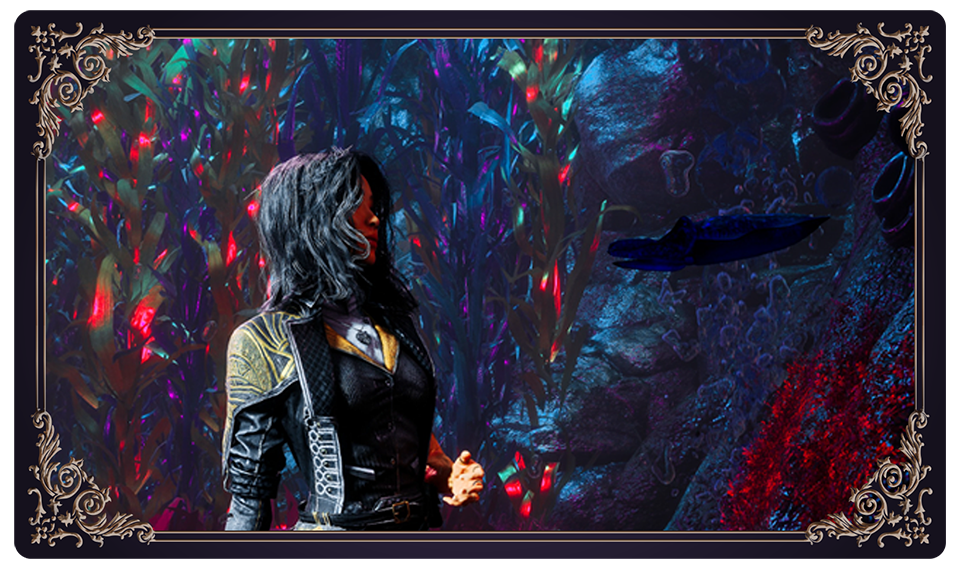

Clair Obscur: Expedition 33

If you look at pre-release interviews for the game, there's one word that always comes up: "essence." So what is the essence of a game? I believe it's fun. Regardless of how one evaluates them—whether it's a run-of-the-mill fantasy game or a timeless classic that's still talked about decades later—they are all ultimately crafted with fun as their goal.

The game I want to talk about today, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, is one that comes close to that essence. It pleases the eyes, ears, and hands. It's fun. No further explanation needed.

First, it features stylish dodging and parrying. You might even relive the satisfying trigger mechanic of Final Fantasy VIII as you grip the controller with both hands. There's nothing to complain about. Add in beautiful music, atmospheric artwork, and an engaging narrative. If I had to nitpick, maybe the user experience across platforms or the speed of patches—but these don't significantly affect the fun.

Among the countless games I’ve played, this one easily qualifies as fun. It even teaches you the word putain—which makes it educational, in a way. I even upgraded my hardware with a 21:9 monitor and dual audio setup just for better immersion. I proved it with my wallet. I don’t think any more explanation or critique is necessary.

Unfortunately, games are constantly expected to justify their existence by being attached to artistic, cultural, or industrial-technological value. The pressure has become so intense that gamers themselves now feel the need to add unnecessary commentary from the realms of humanities, society, and the arts just to talk about a game.

To say, “This game is fun” or “This game is good” to the mainstream, one must dress it up with all kinds of academic jargon. At first, it was about industrial and cultural value. Now, even emphasizing artistic merit doesn’t seem enough. So people start adding ornate adjectives, philosophical arguments, even auteurist and dogmatic perspectives. It often ends up distorted or misrepresented.

While games are being studied as a medium, paradoxically, their connection to “popular hobbies” and “popular culture” is being severed. At some point, appreciation for the game's pure “purposeless purposiveness” disappeared. The rhythm and immersion of gameplay itself are overlooked.

The purpose of games is undeniably play. Games embody the aesthetics of “pure uselessness” better than anything else. They are structurally and orderly, despite serving no function. Playing a game has nothing to do with survival or gain. One might think of “pro gaming for a living,” but let’s set that distortion aside for now.

As mentioned earlier, Clair Obscur is simply a fun game. But this explanation is for those who need more than that—for those who believe that even though games are already widely consumed cultural products, we still need to campaign that “games are culture.” For those who think games must be as artistic and beautiful as film or literature, and pile on adjectives like “cultural convergence” and “technological-humanistic fusion” to justify and validate the game industry.

If you're just someone who plays games because they’re fun, then go ahead and play—it’s fun. Clair Obscur perfectly embraces uselessness. After finishing it, you might think, “Oh, so that’s what this was really about.” Just a heads-up: this article contains light spoilers. If you're sensitive to story details, maybe finish the game first.

Clair(Brightness)

Unlike most other games, what first greets the player here is the music. It makes no effort to hide its intention to tell the story through sound alone. In this game, music plays a central role. It connects the player emotionally to the game through song, from the very beginning to the very end.

To put it grandly, Clair Obscur is an exploration of existence and loss. At its core lies the theme that all existence has light and shadow. This humanistic fragrance fills the speakers and screen with a rich, sensory atmosphere.

Contrast holds deep meaning in this work. The duality of existence runs throughout the game. The game world speaks through sound, like how a song by Young Turks Club might remind you of your first love and dumplings, or how the Parasite OST “Belt of Faith” evokes a strange but warm memory totally disconnected from its haunting tone.

The music delivers the story through a structure and lyrics that match the game's title, Clair Obscur, drawing the player into deep immersion.

"Clair-obscur" is the French expression for the art term "chiaroscuro"—a technique using strong light-dark contrasts. It’s a compound of the Italian words chiaro (light) and oscuro (dark).

This technique uses intense contrast between light and dark to express depth and dimensionality. It adds dramatic effect and is excellent for emphasizing mood or emotion, giving a sense of space on a flat surface.

The in-game music also embodies this chiaroscuro through sound. It’s never monotonous—it shifts constantly in texture and tone, weaving rhythm through contrasts: high and low notes, harmonious and dissonant chords, classical orchestration and jarring electronic noise.

This isn't just sound design—it's a musical translation of the game’s ontological themes. If it were just a few fitting tracks, it’d be good music. But considering that 33 of the hidden items are records, the game’s commitment to music is undeniable.

Hans Zimmer, the legendary film composer, found it extremely difficult to create OSTs for games. Unlike movies, which follow a linear timeline and allow the composer to control the viewer’s emotions, games are shaped by the player's decisions, actions, and pacing. Even if you try to build up emotional tension, the player might suddenly go looking for a hidden item or get lost, breaking the flow of the music. That’s why his work on games like Call of Duty or Bless feels quite different from his film scores.

Film music guides the viewer’s emotions, but game music must instead allow for emotional possibilities—within limits. But Clair Obscur feels like a world painted by a single artist. The music blends in seamlessly, like dripping paint or brushstrokes bleeding across the canvas.

The music not only sets the mood but adds an emotional layer to each scene. While it relies on full orchestration or chamber ensembles, it avoids purely classical melodies. Instead, it introduces unusual, experimental harmonies and emotional ruptures in timbres. In addition to sweet melodies, they lay in dissonance, trembling low strings, and dramatic brass roars to build anxiety and tension. Some vocals are sung in an artificial language, adding a surreal touch. It mixes strange electronic textures to create a sense of “grotesque beauty.”

One representative track from the official OST is “Lumière.” The chamber ensemble—comprising two violins, viola, two cellos, contrabass, and piano—paints the starting city of Lumière through sound.

It begins with a calm piano melody, created by layering 12 different piano timbres. Midway through, strings join in, lifting the emotional line. It conveys both the energy of the city and the hidden unease beneath it.

The rhythm is slow and unstable, but captivating. The score often uses minor keys or the Phrygian mode, creating a surreal, slightly eerie atmosphere.

Modes were used in Western music before major/minor scales became standard. Recently, they’re used in pop music to break away from the monotony of traditional harmony. The Phrygian dominant scale is common in Spanish and Arabic folk music, evoking strong and unsettling emotions. It vividly portrays the atmosphere of a city awaiting *gommage, without a single word of text—what better tool could there be?

Gommage, in the game’s story, is a phenomenon where when the Paintress carves a number onto the monolith, people of that age or older instantly vanish in a swirl of smoke and petals. |

In the latter half, a choir floods the score, reaching an emotional climax. Sustained string notes and choral reverberations leave a strong impression. The grandeur evokes Baroque or Renaissance religious music, but delivers a twisted, dystopian edge. The composition closes with a hot gasp, as if foreshadowing the city's history and fate.

After listening, players can clearly feel the city's identity and atmosphere. The music delicately expresses the coexistence of light and darkness, beauty and unease. It subtly reflects the game’s world and themes, instilling both anticipation and anxiety.

As Koreans, we don’t really understand French—so luckily, we miss the fact that the lyrics are actually full of spoilers. Knowing only something like “Céline Tran” may have helped us stay more immersed in the game. That’s a relief.

Music also serves a narrative function. It performs like an actor while the characters fade into the background. Music fills the silence between dialogue and battles. The ambient sound you hear when entering a new area isn’t just for setting the mood—it hints at the location’s history and hidden tragedies.

When you enter a location tied to a past massacre, the music gives way to silence—as if the sheet music has been erased. When the distorted choir kicks in, it feels like the fear comes not from the moment itself, but from something ancient and deeply rooted in memory.

It fits the saying that music speaks the truth before words—and buries the truth long after the words are gone.

The track “Alicia” musically encapsulates the identity and emotional core of the game. Like other pieces, it was composed by Lorien Testard and features vocals by Alice Duport-Percier. It conveys melancholy and nostalgia, while also offering hope and elevation. It transcends background music—it resonates with the game’s worldview and emotional weight.

OSCURO(Darkness)

The chiaroscuro technique used in Clair Obscur emphasizes depth in characters and objects through contrast. But it goes beyond mere tonal differences—it visually conveys emotional depth and dramatic tension. You don’t even need an OLED screen to see it perfectly; an IPS or VA panel will do. You’ll feel it in your chest regardless.

Clair Obscur follows an expedition into unknown lands. But their journey isn’t one of conquest—it’s more like a pilgrimage to understand their own reason for being. Eventually, the expedition reaches its destination, but they don’t find a treasure or secret. The player realizes that the journey itself was a search for life’s essence.

The narrative structure of Clair Obscur is quite unique. Acts I and II follow a traditional heroic route and offer enjoyable gameplay, but then Act III introduces questions open to interpretation—and leaves a lingering sense of reflection.

Naturally, players may feel confused by this sudden tonal shift. Though clearly intentional, many of the characters who provided joy early on are sidelined, and the character relationships start to unravel. The main character switch isn’t handled smoothly—most of the game is spent with the expedition members, after all.

Then suddenly, the game starts infodumping in an almost Buddhist “limitless void” style, forcing players to shift emotional gears—naturally causing disorientation.

But from the lens of contrast, this too seems like an intentional structural device. The developers likely had to make tough choices to avoid a bloated, messy, or overly academic storyline. By clearly separating Acts II and III, they could twist the narrative canvas to convey “the weight of being,” adding emotional dimensionality. This chiaroscuro invites empathy through subtle emotional shifts.

If we read into it further, it’s an artistic device that shapes philosophy, emotion, and the depths of existence. You need darkness to see light, and light to see darkness—and the story begins in the space between. It symbolizes internal duality, or the coexistence of light and dark.

The game’s ending aligns with Albert Camus’ existential absurdism. Humans endlessly seek meaning in existence, only to confront its ultimate meaninglessness. The expedition accepts this absurdity and embraces truth. What mattered was not the destination but the journey itself, through which they affirmed their existence.

Beneath the flashy action and thrill of victory lies a contrasting question posed to the player: the fundamental inquiry—what is existence?

33 EXPEDITION

While playing, I kept wondering—why the number 33? In line with the game’s mysterious atmosphere, I decided to take a numerological approach. Sure, we live in a time when no one seriously believes in things like how Ilsan’s streets run wider east-west than north-south, or that apartment kitchens in Apgujeong are aligned for gun placements. But just to clarify: numerology is a philosophical and mystical school that explores the hidden meanings of numbers.

From a numerological viewpoint, the number 33 signifies completion and enlightenment. It symbolizes wholeness, salvation, and transcendence. It also represents compassion, healing, and spiritual awakening. Each of these aligns closely with the themes of the game.

In numerology, 11, 22, and 33 are unique—they carry distinct meanings. Among them, 33 is known as a “Master Number,” carrying especially strong and sacred significance.

When creators use specific numbers, it’s often intentional—to reinforce a message. The fact that the battle party has three members, and that the title contains “33,” seems deeply connected to the game’s themes. Even the stark contrast between Acts I/II and Act III could be a symbolic gesture. The game’s core ideas about accepting and transcending existence resonate with the symbolism of 33—or perhaps vice versa.

From a more conspiratorial perspective, 33 is often seen as a world-shaking number. Some claim it’s hidden in major events—JFK was assassinated on November 22 (11+22=33), and Jesus was crucified at age 33. Thus, 33 is associated with the complete lifespan and ultimate sacrifice.

Mystical groups like the Freemasons also assign deep meaning to 33. Their highest degree is the 33rd Degree, symbolizing enlightenment, spiritual fulfillment, and supreme wisdom. It's an honorary rank, granted only to the chosen few—fueling the idea that 33 represents elite secret societies that rule the world.

33 is also seen as an Illuminati symbol, said to represent the number of elite figures secretly ruling the world. “Council of 33 Judges,” “33 Clergy of Judgment”—these names pop up frequently in conspiracy videos and documents.

In the game, the protagonists’ journey is not just about victory or defeat—it’s about completion and salvation. So the number 33 becomes a symbolic device that encapsulates the game’s world and its characters’ fate. It delivers a deeper message of reflection to the player. It’s not just about being 33 years old.

From the perspective of illuminating life’s paradoxical and contradictory nature, contrast is found not in answers but in questions—not in certainty but in ambiguity. Interpretations may vary, but the game’s deepest message completes a humanistic insight: life is not about the result, but the journey, and meaning is not something found in answers, but something formed while holding questions along the way.

“Get famous first. Then anything you make will be called art.”

This quote is often attributed to American artist Andy Warhol, but it’s actually apocryphal. The source is unclear, yet the phrase functions both as a satire of the media industry and a provocation about modern art. Despite being fake, it continues to resonate with people’s conflicted feelings about art today.

As I said at the beginning, my evaluation of Clair Obscur ends at “it’s fun.” And yet, I’ve gone on this long, academic ramble just to offer some justification and packaging for those unfamiliar with games—to convince them that this is a “great game.”

French President Emmanuel Macron praised the game’s developers, saying, “You are a shining example of France’s boldness and creativity.” This from a politician who once blamed video games for France’s civil unrest. Politicians reversing their stance is as common as seeing your son as more handsome than Cha Eun-woo, but a president openly endorsing a video game? That’s noteworthy.

It would be like the Korean president saying in a public speech, “Nikke’s illustrations are the Mona Lisas of our time,” or a headline declaring, “President to invest 20 trillion won yearly in game industry clusters to become global #1.”

Looking back, games were hardly ever mentioned positively in public discourse. At best, they were blamed for “random crimes” or brought up in passing by the Prime Minister’s Office.

Positive coverage of Korean content has always gone to K-pop, dramas, or films. Leaders mention Squid Game or BTS; ministers mention young international piano competition winners. The media still focuses on foreign girls dancing to K-pop in Nami Island, but games? They’re only referred to in vague, ceremonial language—if at all.

There was a time when people shouted, “Games are the culmination of art!” Just as painting and sculpture weren’t considered art until the Renaissance, and photography, film, and comics were only accepted in the 20th century—games were declared to be interactive total artworks combining visual art, music, film, and literature.

Even now, many arguments try to prove games’ usefulness by emphasizing their social, political, or educational impact—hoping to earn them artistic recognition. And yes, games do seem capable of delivering on those fronts.

But none of this truly answers the core question: why do players play games? Do people really sit in front of a screen for hundreds of hours to pursue social and political enlightenment?

So yes, the reason for all this long-windedness was just to say: Clair Obscur is fun. You don’t need to invoke chiaroscuro, Phrygian modes, or Camus to enjoy or understand it.

You don’t need to grit your teeth and wave the artistic or cultural flag. You don’t need to cite its export value. You can just talk about combat, the characters, the story—and that’s more than enough to explain this game.

If we were truly a strong eSports nation, we wouldn’t need to shout about being a “birthplace of eSports.” If it’s truly culture, truly art, we wouldn’t need to scream to prove it. If it’s fun, that’s enough. A fun game deserves fun stories to be told around it. In a time filled with flashy, self-replicating games, the arrival of a truly good one feels refreshing. Even without explaining its intentions, people will find meaning and talk about it. Fun is enough. That’s the essence of games.

TOP

TOP